Mrs. Callahan stood before us, wearing one of the many theme sweaters from her wardrobe. All of Mrs. Callahan’s sweaters were works of misguided creative abandon. They made their first appearance right around Halloween, when she strolled into our fifth grade classroom wearing a cardigan emblazoned with a witch on a broomstick, cackling as she crossed a full moon. I quickly sketched the design so I could describe it in full, glorious detail when I got home. But the witch sweater was no fluke. In the ensuing weeks and months, Mrs. Callahan would reveal the full extent of her theme sweater collection. Scary sweaters led to harvest time, with cornucopias cascading nature’s bounty across her breasts, then pilgrims brandishing muskets on her back, and of course, the holiday sweater spectacular. It was impossible to listen to a word the woman said the entire month of December. Every time she turned her back to write on the blackboard, we would be greeted by a gleeful Santa, a frolicking reindeer, or the entire cast of the Nativity, ‘round yon Virgin.

It was now January, and Mrs. Callahan was wearing a relatively subdued snowflake sweater. It was safe to assume that this was merely her wardrobe pausing for breath before the Valentine’s Day series in our near future.

"Class," said Mrs. Callahan. "I have a very exciting assignment for all of you. I want you all to read a book, any book you’d like, and then give a one-page book report. But, for this book report, I would like you to present it..."

She paused, letting the suspense build.

"AS A CHARACTER FROM THE BOOK!"

She was quaking with excitement. She had implemented a whole new method of book-reporting, perhaps gleaned from an article she read in American Teacher while airing out the week’s sweaters.

My mind reeled with possibilities. I had recently stolen my sister’s copy of Flowers in the Attic, and thought it might be nice to play one of the children who died of arsenic poisoning. There was also a legion of characters from Steven King novels, but I was certain someone else would do that.

And then it hit me. The performance that would surely impress all of my ten-year old classmates beyond words, and finally reveal the depths of my talent:

It was now January, and Mrs. Callahan was wearing a relatively subdued snowflake sweater. It was safe to assume that this was merely her wardrobe pausing for breath before the Valentine’s Day series in our near future.

"Class," said Mrs. Callahan. "I have a very exciting assignment for all of you. I want you all to read a book, any book you’d like, and then give a one-page book report. But, for this book report, I would like you to present it..."

She paused, letting the suspense build.

"AS A CHARACTER FROM THE BOOK!"

She was quaking with excitement. She had implemented a whole new method of book-reporting, perhaps gleaned from an article she read in American Teacher while airing out the week’s sweaters.

My mind reeled with possibilities. I had recently stolen my sister’s copy of Flowers in the Attic, and thought it might be nice to play one of the children who died of arsenic poisoning. There was also a legion of characters from Steven King novels, but I was certain someone else would do that.

And then it hit me. The performance that would surely impress all of my ten-year old classmates beyond words, and finally reveal the depths of my talent:

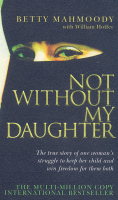

I would portray Betty Mahmoody, the heroine of the spellbinding memoir Not Without My Daughter.

I’d found the book on my mother’s nightstand, and was quickly enthralled with the story of an American woman trapped in Iran by her abusive monster husband, and forced to overcome seemingly insurmountable odds to escape with her beloved little girl. This, I knew, would be the most powerful book report the fifth grade had ever seen.

I spent the next week crafting my performance, going through multiple drafts of Betty’s emotional monologue, in which I would recount the details of my harrowing escape while cradling a Cabbage Patch doll. I told my family nothing about the project, fearing they might try to interfere with my creative process.

My sister Shannon drove me to school on the day reports would be presented. The doll was in my backpack, as was a navy blue bedsheet I intended to wear as a burkha. Finally, I could contain my enthusiasm no longer. As we pulled into the drop-off lane at Upper Elementary, I told her all about my impending premiere. Her reaction was unexpected.

I’d found the book on my mother’s nightstand, and was quickly enthralled with the story of an American woman trapped in Iran by her abusive monster husband, and forced to overcome seemingly insurmountable odds to escape with her beloved little girl. This, I knew, would be the most powerful book report the fifth grade had ever seen.

I spent the next week crafting my performance, going through multiple drafts of Betty’s emotional monologue, in which I would recount the details of my harrowing escape while cradling a Cabbage Patch doll. I told my family nothing about the project, fearing they might try to interfere with my creative process.

My sister Shannon drove me to school on the day reports would be presented. The doll was in my backpack, as was a navy blue bedsheet I intended to wear as a burkha. Finally, I could contain my enthusiasm no longer. As we pulled into the drop-off lane at Upper Elementary, I told her all about my impending premiere. Her reaction was unexpected.

She began to cry.

"Oh, God, Topher. Please, please, do not do this. Everybody already makes fun of you, and they make fun of me because of you... They always ask me why my brother’s so weird, and I try to say you’re not, but then you pull stunts like this..." her voice trailed off.

"But I have to," I said. "It’s for a grade, and it’s all I prepared."

"You read all the time, you can do another book," she said. "A real kid’s book. And be a boy. Please. You’re making things so much harder for yourself."

We sat in the Camaro in silence. I knew my classmates told their older siblings about the bizarre shit Topher Payne was always doing. I knew my sister caught hell for it, and in their own way, so did my parents. I felt awful.

"Okay," I said. "I’ll be Encyclopedia Brown."

Later, I sat in Mrs. Callahan’s class, my Trapper Keeper holding the report on a Beverly Cleary book I’d hastily scrawled in the cafeteria. I watched my classmates, one by one, doing their mediocre interpretations of The Babysitter’s Club and the Hardy Boys. I tried so hard to fit in with these people. I’d played baseball, joined Cub Scouts, and suffered through year after year of Summer Day Camp, all in a fruitless attempt at blending with the majority. And for whatever reason, it hadn’t worked. I was different, and I’d always known it.

"Oh, God, Topher. Please, please, do not do this. Everybody already makes fun of you, and they make fun of me because of you... They always ask me why my brother’s so weird, and I try to say you’re not, but then you pull stunts like this..." her voice trailed off.

"But I have to," I said. "It’s for a grade, and it’s all I prepared."

"You read all the time, you can do another book," she said. "A real kid’s book. And be a boy. Please. You’re making things so much harder for yourself."

We sat in the Camaro in silence. I knew my classmates told their older siblings about the bizarre shit Topher Payne was always doing. I knew my sister caught hell for it, and in their own way, so did my parents. I felt awful.

"Okay," I said. "I’ll be Encyclopedia Brown."

Later, I sat in Mrs. Callahan’s class, my Trapper Keeper holding the report on a Beverly Cleary book I’d hastily scrawled in the cafeteria. I watched my classmates, one by one, doing their mediocre interpretations of The Babysitter’s Club and the Hardy Boys. I tried so hard to fit in with these people. I’d played baseball, joined Cub Scouts, and suffered through year after year of Summer Day Camp, all in a fruitless attempt at blending with the majority. And for whatever reason, it hadn’t worked. I was different, and I’d always known it.

And I was so fucking tired of running from it.

"Topher," Mrs. Callahan said, a snowman waving at me from her torso. "It’s your turn."

I rose from my desk, removed the sheet and doll from my bag, and approached the blackboard. I wrapped myself in the sheet and faced my peers.

"My name is Betty Mahmoody. My husband held me prisoner for eighteen months in Tehran. He beat me every day. I wanted to run away, but... not without my daughter."

I told them of my demoralizing experiences in a foreign land, and described in vivid detail my escape via Arabian horseback into Turkey.

"I found my inner strength," I concluded. "I got away."

Here, I pulled my child close to my breast and had a private moment, reflecting on all I had overcome. I looked up, at the blank stares from my classmates. Mrs. Callahan was completely nonplused.

"...thank you, Topher," she said at last. "You may take your seat."

All of my sister’s warnings proved devastatingly accurate. At recess that afternoon, I was taunted and bullied more than ever. A huddle of teachers engaged in discussion, occasionally gesturing to me. But it didn’t sting as much as it usually did. It felt as though my skin had thickened, ever so slightly. I was no longer seeking their approval. I knew their opinions of me were not likely to improve, so why waste my time? Although I didn’t know it at the time, I was experiencing the first stirrings of personal pride.

It is my great fortune to live in a time and place where people with stories like mine (okay, not JUST like mine, but equally bizarre) gather together in a celebration of what makes us so damn special. And while the strides our community has made in mainstream culture should be recognized and honored, that’s not what Pride’s all about for me.

What I love about Pride is the feeling that, despite all odds, we are a community that is unapologetic about being ourselves. We chose not to assimilate, thus ignoring the weird, wonderful elements that define us. It was not an easy path in life. Many of us have been forced to forfeit the families, friendships, careers, or religious beliefs that we were told would sustain us. But one weekend a year, we gather and remind each other that it was worth it, and we have each other.

The ten year-old in me rejoices every year when I see, to my great relief, that it is not just me.

"Topher," Mrs. Callahan said, a snowman waving at me from her torso. "It’s your turn."

I rose from my desk, removed the sheet and doll from my bag, and approached the blackboard. I wrapped myself in the sheet and faced my peers.

"My name is Betty Mahmoody. My husband held me prisoner for eighteen months in Tehran. He beat me every day. I wanted to run away, but... not without my daughter."

I told them of my demoralizing experiences in a foreign land, and described in vivid detail my escape via Arabian horseback into Turkey.

"I found my inner strength," I concluded. "I got away."

Here, I pulled my child close to my breast and had a private moment, reflecting on all I had overcome. I looked up, at the blank stares from my classmates. Mrs. Callahan was completely nonplused.

"...thank you, Topher," she said at last. "You may take your seat."

All of my sister’s warnings proved devastatingly accurate. At recess that afternoon, I was taunted and bullied more than ever. A huddle of teachers engaged in discussion, occasionally gesturing to me. But it didn’t sting as much as it usually did. It felt as though my skin had thickened, ever so slightly. I was no longer seeking their approval. I knew their opinions of me were not likely to improve, so why waste my time? Although I didn’t know it at the time, I was experiencing the first stirrings of personal pride.

It is my great fortune to live in a time and place where people with stories like mine (okay, not JUST like mine, but equally bizarre) gather together in a celebration of what makes us so damn special. And while the strides our community has made in mainstream culture should be recognized and honored, that’s not what Pride’s all about for me.

What I love about Pride is the feeling that, despite all odds, we are a community that is unapologetic about being ourselves. We chose not to assimilate, thus ignoring the weird, wonderful elements that define us. It was not an easy path in life. Many of us have been forced to forfeit the families, friendships, careers, or religious beliefs that we were told would sustain us. But one weekend a year, we gather and remind each other that it was worth it, and we have each other.

The ten year-old in me rejoices every year when I see, to my great relief, that it is not just me.